How I Think About Valuation

This is a post from 2021 from my old personal blog. I think it summarizes how I think about valuation quite well.

I used to think of valuation as a very precise science. I now realize it is an imprecise art, but it’s critical to think when determining a stock’s future returns and should be carefully considered before purchasing a stock.

Value vs. Growth: An Abstract Debate

Value vs. growth. It’s an abstract concept.

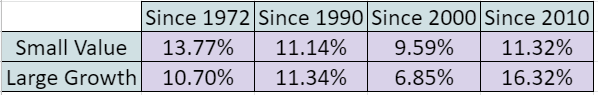

We can do back tests and show how the academic factors perform.

Over the long haul, value – particularly small value – beats growth.

For the last decade, growth beat value.

The decade before that, value beat growth.

Side note: I do think it’s funny that small value’s terrible decade has been an 11% CAGR. A great result in my book. Only bad in relative terms.

I think it’s important to take a step back away from that debate and think about it on a micro level. What impact do growth rates have on returns? What impact do changes in multiples have on returns?

Lately, everyone has been worshiping growth. It’s obviously a component of the return when holding onto a position for a long period of time.

Sources of Long-Term Returns

I thought it would be good to think through some examples of what could happen with different companies based on the price paid at different growth rates.

Returns from a stock is going to be derived from some basic variables. Growth is obviously a key factor, but the price paid is also critical.

There are three basic sources of return on a common stock investment:

Multiple expansion/contraction

Growth/decline in fundamentals

Dividends

There is a lot that goes into determining all of these variables. Dividends may not be sustainable. Sometimes dividends don’t make sense from a capital allocation perspective. Earnings growth can be boosted with buybacks. Growth can be destructive in some situations (such as when it is fueled share issuance or via debt and it doesn’t generate ROIC that exceeds WACC). Growth is difficult to predict.

For a high growth firm, it’s important to consider the base case. It is often difficult for a company to sustain a fast rate of growth.

The future is very hard to predict. What will earnings be? How will the earnings growth be achieved? Will return be derived from dividends? What multiple will investors be willing to pay in the future based on the company’s prospects, interest rates, or Mr. Market’s mood?

As active investors, though, we have to make some educated guesses on all of these points. Having some expectations and opinions about all of these things is essential for the purchase of individual stocks.

When it comes to earnings multiples, it is extremely difficult to predict. For me, I think it’s best to be conservative. If it’s a high P/E – assume it will eventually mean revert to a median P/E.

I don’t think many people paying sky high multiples are really thinking through the implications of this.

Price is what you pay, value is what you get

Let’s think through an example: a growth company that can grow at a 20% rate.

A 20% growth rate puts a company in the top tier of stocks. Adobe, for example, has been able to grow EPS at a 22% CAGR for the last 10 years. Most companies don’t grow that fast and few can sustain that kind of pace for a long period of time.

A lot of people would think that a 20% growth rate would be able to overcome a high price. After all – a 20% CAGR turns $10,000 into $61,917 after 10 years.

Surely, when investing in a company with that level of growth, the price paid is of little consequence. Right?

Unfortunately, in the public markets, you have to figure out what to pay for that growth rate. You not only need to figure out the company’s future growth rate, but you also have to figure out if you’re paying a reasonable price. The price paid and the growth rate are going to determine your return from the investment.

“Reasonable” price is a hard thing to figure out. It’s particularly difficult because it’s a measure of Mr. Market’s emotional temperament. In 2016, the market thought that Apple was worth a 10 P/E. Today, they think it’s worth 36. It’s pretty much the same company that it was in 2016, but the market perceives it differently.

So, you not only have to think about the growth rate of the company, but you also have to think about what the multiple will be in the future. Will it contract? Will it expand?

I think it makes sense to be conservative. After all, every company has a lifecycle. As it matures in its lifecycle, it ought to be cheaper. It’s going to shift from a fast-grower into a more steady grower. Therefore, if someone is paying sky-high multiples, it’s probably safe to assume that the multiple contracts as the company matures.

On the flip side, if you’re buying a dirt cheap stock and you actually think it’s going to grow in the future (i.e., it’s not a buggy whip destined for failure, but the market misunderstands the company and it will grow in the future) – then it is probably safe to assume you’ll get some modest multiple appreciation if you’re right about the company’s prospects.

There are also drivers of multiples that are impossible to predict. The key example of this is interest rates. Contrary to popular belief, it is possible for interest rates to increase. If they do ever go up again, then a 10-year treasury bond paying 10% interest with zero default risk is a lot more appealing than a slow growing stock with a 2% earnings yield. Earnings yields are going up. Put differently, P/E ratios (and stock prices) are going down.

Of course, interest rates are impossible to predict. Most people in 2010 assumed interest rates were headed higher and they were wrong.

The economic cycle also impacts multiples. In a recession, everyone is convinced that the world is ending and they’ll give away stocks for bargain prices. In a boom, everyone is convinced that gold will soon rain from the heavens and they’re willing to pay sky high multiples. Predicting the economic cycle is even harder than predicting interest rates. Ask any perma-bear who has been predicting the apocalypse since 2010.

Interest rates, inflation, recessions/prosperity – they’re pretty much impossible to predict. I’ve tried. So, I think it’s best ignored when evaluating a company.

Because many of the factors impacting multiples are unpredictable, then I think a good way to approach this is also through the perspective of conservatism. Assume the multiple will contract. Assume rates will go up. How will that impact the company’s balance sheet and cash flows?

Assume that a recession will happen tomorrow and try to figure out how that will impact the company’s finances.

Exhibit A: A Growth Company

Let’s go back to the 20% example. What happens if the 20% grower is bought at a P/E of 50? What happens if the multiple contracts to a P/E of 20?

Rather than look at this through mathematical abstraction, I thought it would be best to think about this company and show all of the variables, year by year.

This is the result:

Even with the multiple contraction, this works out just fine. In this theoretical example, an investor turns $10,000 into $24,766.95.

Not bad, but this is a long way off from a true 20% CAGR – which would have turned $10,000 into $61,917. The multiple contraction was expensive.

You also made a big assumption – that the company could grow by 20% for a decade. A 20% rate of earnings growth is extremely hard to sustain. That sort of growth rate puts a company in the absolute top tier of companies.

Microsoft grew EPS at a 10.6% CAGR over the last decade. Adobe has been able to grow at a 22% rate over the last decade. Apple has also been able to grow at a 19.7% rate.

Most companies cannot grow that fast.

It’s also dangerous to extrapolate a 20% growth rate forever into the future. For most companies, growth ultimately slows down as they mature in their development.

So, it’s probably safe to assume that the Adobes of the world will eventually slow down.

Therefore, what happens to our hypothetical 20% grower if it turns into a 10% grower? Let’s still assume that the 50 P/E contracts to 20. The multiple contraction is probably much more realistic in this scenario. After all, if the company is slowing down, investors won’t be willing to pay such a high price.

In that scenario, this is the result:

This stock has been dead money for 10 years. A 10% growth rate (a very respectable return) should have turned $10,000 into $25,937 after 10 years. Instead, in this example, the multiple contraction left you with $10,374.97.

The only way this works out is if the company maintains a high multiple.

Unfortunately, that’s simply not a realistic expectation. Multiples fluctuate for all sorts of reasons. An investor has to be conservative in these assumptions, because a multiple can contract as fast as it goes up.

Real World Examples

Here is a chart of the P/E ratio for Home Depot. It’s one of the biggest companies in the USA. Everyone follows it. It’s a Dow component.

Even though Home Depot is widely followed in the market, the multiple changes in chaotic ways. Was it actually worth a 11x P/E after the financial crisis? Was it worth 40x when everyone was convinced we were in a “new economy” of never ending prosperity in 2000?

The volatility in the multiple is astounding considering the stability of Home Depot’s business.

If Home Depot’s multiple changes this much – what do you think is going to happen to a microcap? What do you think is going to happen to a company in a fast changing industry? If multiples are volatile for big, predictable businesses – then it is probably best to be conservative in one’s assumptions about what that multiple will be in the future for any company.

Here is another example: Hershey. Is candy a complicated business? Mr. Market seems to think so:

In 2015, Mr. Market thought that Hershey was worth 37x earnings. In 2009, 18x.

If multiples for a candy stock are this volatile – what do you think will happen to a more complex business? What do you think will happen to a high flier when the growth rate slows down a bit?

My philosophy is: best to be conservative with those assumptions.

Exhibit B: The Boring Value Stock

Now let’s think of a “boring” company. A company that grows by only 5% a year. Basically, a bit more than nominal GDP.

A 5% growth rate turns $10,000 into $16,288 by the end of 10 years. A growth investor would scoff at this. Why would you even bother with a company that has such a low growth rate?

Well, let’s say it is purchased at a P/E of 10. The P/E goes up to 15 over the next 10 years. What happens then?

The $10,000 investment turns into $24,433.42. That is a 9.34% CAGR.

This boring company growing at only 5% per year with some modest multiple appreciation winds up a beating the 20% grower that had some multiple contraction.

It’s also worth considering: this boring company probably pays a dividend, too. On top of that 9%, you might be able to squeeze out another 2% via dividends.

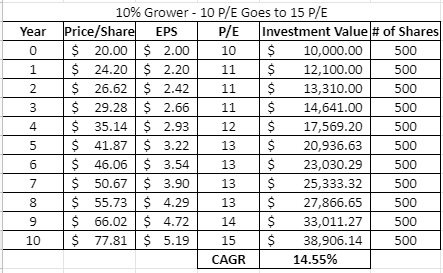

Now, what if it doesn’t grow by 5? What if it can grow by 10%?

Now, you have an extraordinary result. This is the sort of thing I am looking for. This is a “wonderful company at a wonderful price.” An investor earned a 14.55% return in this situation. This was like buying Lockheed during the 2011 budget showdown, or Microsoft in 2012, or Apple in 2016.

As mentioned earlier, this investor probably earned some dividends on top of that.

Of course, not all value stocks are going to grow. In fact, many are going to be buggy whips and value traps and cheap for good reason. The retailer headed for oblivion. A cyclical that’s about to be annihilated. I’ve bought a lot of these.

It’s hard to figure out whether the market is right about a cheap stock. On the other hand, it’s equally hard to figure out if a current market darling is going to continue to grow at a rapid pace.

It’s almost as if active individual stock investing is hard and requires critical thinking.

Return Assumptions

In my view, it’s essential to define these assumptions before buying a stock.

How much are you going to earn in dividends? For a stable business (like Hershey), this is probably the easiest thing to figure out.

What will the growth rate be? This one is much harder. For the growth component, it’s probably best to be conservative. Companies can’t grow at 20% forever. Personally, I like a company that grows revenues with nominal GDP and earns high returns on capital with excess cash that can be returned to me via dividends and buybacks.

What will the multiple be in the future? This is the hardest of all. It’s probably best to be conservative there, too, considering the volatility in multiples for even widely followed stocks with simple businesses.

The growth investors are right in the sense that the growth rate can’t be ignored. It’s going to be very hard to make money in the long run off a no-growth company. It’s going to be nearly impossible to earn money off of a company in decline unless it can be flipped quickly for the “one free puff.”

Value investors are sometimes blinded to this reality.

Where the growth investors are blinded is assuming that the price paid is irrelevant to the return. It most certainly matters. It’s one of the key drivers of returns.

It matters even more because – over time – multiples are extraordinarily volatile and it’s a safe assumption that a high multiple will mean revert as companies mature.

Also keep in mind I’m talking about earnings.

For investors paying 29x SALES (the current valuation on Tesla) – it’s going to be practically impossible for an investor to generate positive long-term returns from a stock like that if the multiple contracts. How fast can Tesla grow? What price/sales multiple will investors give Tesla in the future? It takes some wild (nearly impossible) assumptions to see how this works out in the future.

Amazon is probably the best example of a high growth company. They have been able to grow sales by nearly 30% for 20 years. That is an extraordinary result that makes it one of the best companies in the history of markets. It’s worth considering, though, that the most expensive Amazon has been since 2001 is 5x sales.

Have you actually found the next Amazon? Seems unlikely. Amazon is one of a kind. There aren’t really any companies that can sustain 30% growth rate for 20 years. Amazon is special. Is your company special? Maybe. The base case is not on your side, though.

When looking at companies trading at extremely high sales multiples, it’s clear to me investors aren’t thinking through any of these variables right now.

What are the macro implications of this? I haven’t the slightest idea.

I do know that at a micro level, it’s going to be nearly impossible for many of these stocks to generate returns if they have even the slightest mean reversion in price.

If you enjoyed this free article, please consider a paid subscription to this substack. I will profile one company at least once a month in an effort to understand deeply all 500 companies in the S&P 500 for investment purposes. I am building a watchlist of ‘wonderful companies,’ monitoring them, and buying them for my personal portfolio when they hit attractive valuations.

Disclaimer

Nothing on this substack is investment advice.

The information in this article is for information and discussion purposes only. It does not constitute a recommendation to purchase or sell any financial instruments or other products. Investment decisions should not be made with this article and one should take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular person or institution.

Investors should obtain advice based on their own individual circumstances from their own tax, financial, legal, and other advisers about the risks and merits of any transaction before making an investment decision, and only make such decisions on the basis of the investor’s own objectives, experience, and resources.

The information contained in this article is based on generally-available information and, although obtained from sources believed to be reliable, its accuracy and completeness cannot be assured, and such information may be incomplete or condensed.

Investments in financial instruments or other products carry significant risk, including the possible total loss of the principal amount invested. This article and its author do not purport to identify all the risks or material considerations that may be associated with entering into any transaction. This author accepts no liability for any loss (whether direct, indirect, or consequential) that may arise from any use of the information contained in or derived from this website.