Deconstructing Warren Buffett's Apple Sale

Buffett’s Sale of AAPL

Warren Buffett's recent decision to reduce Berkshire Hathaway's Apple stake has caused quite a stir. Originally, the Apple position had grown to represent over 50% of Berkshire's portfolio, but after Buffett sold more than $80 billion worth of shares, it now comprises just 25%. The sheer size of the sale understandably caught people's attention.

As soon as the news hit social media, reactions were swift and, predictably, exaggerated. The Motley Fool posed the question, "Could This Be the Biggest Investing Mistake He's Ever Made?"—a sensational headline that later the article itself questions. On the other end of the spectrum, Zero Hedge proclaimed "Buffett Calls the Top," fueling speculation that the stock market is in an unprecedented bubble and that Buffett is heading for the exits.

This reaction underscores a major issue with modern financial commentary: the focus has shifted from thoughtful analysis to sensationalism and clickbait headlines.

I think that platforms like Substack stand out because they offer a refuge from this trend, allowing writers to move away from the sensationalism that dominates mainstream financial media and provide more measured, in-depth insights.

In the age of clickbait, the narrative often becomes more about drama than substance.

An Amazing Investment

Before diving into the reasons behind Buffett's decision to sell part of his Apple position, it's important to first understand why this investment was so successful in the first place.

Buffett's investment in Apple ranks among the most remarkable in history. Few companies are substantial enough to impact a giant like Berkshire Hathaway, but Apple was one of those rare exceptions.

Buffett’s universe is limited to a select few giants capable of moving the needle for a company of Berkshire's size. In Apple, he found the perfect "whale"—a stock that not only had the potential for significant returns but was also substantial enough to make a meaningful difference to Berkshire's portfolio.

It’s even rarer for a company of Apple’s size to offer such compelling value—both in terms of its attractive valuation and its outstanding growth prospects. Seeing this unique opportunity, Buffett made a bold move by acquiring a significant stake, one that would profoundly benefit Berkshire shareholders.

Buffett began buying Apple stock in 2016, at a time when it was astonishingly undervalued. By the end of 2015, Apple was trading at just 11.5 times its earnings—a remarkably low valuation for a company of its caliber. Buffett saw this as an opportunity and steadily increased his position throughout 2016 and beyond.

Deconstructing the Return

From 2016 to the end of 2023, Apple stock achieved a remarkable CAGR of 29.8%. What fueled this growth?

Stock returns are driven by three factors:

Growth/Decline in Fundamentals

Shareholder Yield

Changes in Sentiment

Buffett’s investment in Apple encapsulated all these factors. Let's break it down:

Growth/Decline in Fundamentals

Apple's revenue grew from $215 billion in 2015 to $383 billion in 2023, reflecting a 7.48% CAGR. This growth was driven primarily by iPhone sales and the expansion of services tied to those devices.

The iPhone, Apple's flagship product, accounted for 52% of sales and also significantly boosted the services segment, which contributed 22% of sales. The introduction of more premium iPhones further bolstered this growth.

Another significant contributor was the launch of the Apple Watch and Airpods in 2015 and 2016, respectively. By 2023, the “Wearables, Home, and Accessories” segment had grown to $39.8 billion in revenue—a segment that barely existed in 2016.

Of course, the 7.5% sales growth alone doesn’t explain the 29.8% CAGR. What else happened?

Shareholder Yield

Apple aggressively reduced its share count by 30% through buybacks. This significant reduction amplified the impact of the company’s sales growth, boosting the CAGR from 7.5% to 13.1%.

Buffett recognized Apple’s strong commitment to buybacks, which had started in 2013. He saw that the company was now dedicated to repurchasing substantial amounts of its own stock, signaling a shift in capital allocation priorities.

Dividends increased steadily from $0.50 per share in 2015 to $0.94 per share in 2023. Reinvesting these dividends would have further increased the CAGR to 14.46%.

Changes in Sentiment

While the impressive 14.46% CAGR was driven by fundamentals alone, the additional boost to 29.8% came from a significant shift in market sentiment and valuation (i.e., speculative return), adding substantial "icing on the cake" for investors.

The rest of the return can be attributed to changes in valuation. The P/E ratio rose from 11.5x at the beginning of 2016 to 27.45x by the end of 2023, driving much of the stock’s performance. A company delivering a 14.46% return through organic growth and shareholder yield typically wouldn’t trade at just 2.6x sales and a P/E of 11.5x, but that was Apple’s situation in late 2015.

Why were investors so pessimistic about Apple? The narrative at the time, captured well by a short pitch on Value Investor’s Club in 2017, focused on slowing revenues for the first time in years. This decline fueled concerns that Apple was a company in decline, particularly as the iPhone faced growing competition from Android and other rivals.

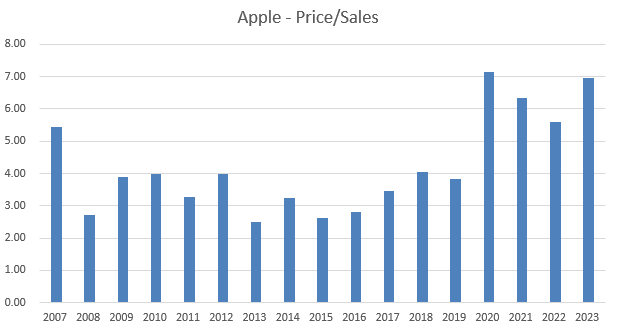

This narrative turned out to be misguided, but it led to Apple trading at the low valuation. Over the following years, investors recognized this misjudgment. By 2019, Apple’s valuation had adjusted to a more reasonable level for a company of its stature, trading at nearly 20x P/E and almost 4x sales.

As sales surged during COVID, the valuation soared even higher and the valuation entered a more manic phase.

You could interpret this in two ways: either investors became manic about Apple, or real improvements in the business justified the higher valuation.

In reality, it’s likely a combination of both.

Let’s take a look at business improvement.

Interestingly, margin improvements didn’t play a major role. Operating margins were 30.5% in 2015 and remained relatively stable, at 29.8% in 2023. Normally, improved margins would drive better returns on capital, but that wasn’t the case here.

What did change was Apple’s financial leverage, which significantly enhanced returns on capital. The debt/equity ratio increased from 54% to 197%, with long-term debt rising from $53 billion in 2015 to $106 billion in 2023, and short-term debt increasing from $10.9 billion to $15.8 billion. The reduction in shareholder equity boosted return on tangible capital employed from 37.7% in 2015 to 51.6% in 2023. This improvement in returns likely contributed to investor enthusiasm.

Additionally, some argue that investors began to better appreciate Apple’s moat. Once users are locked into the iPhone ecosystem, with their data seamlessly integrated across devices, they’re more likely to remain loyal customers. Devices like AirPods further reinforce this ecosystem, making it difficult for users to switch away.

Of course, much of this remains speculative. Investors are a little crazy and get manic from time to time.

This is why I consider changes in valuation multiples to be the "speculative" component of returns. Predicting what price multiple that investors will assign to a company is as unpredictable as the mood swings of Tony Soprano.

Ideally, an investor should see a path to returns without relying heavily on speculative factors.

I suspect that’s the analysis which Buffett conducted in 2016. He saw a depressed stock that could deliver a solid return without needing a major shift in sentiment - and thought that the stock would likely see a shift in sentiment on top of that, anyway.

The Sale

Now, let's address the question: why did Buffett decide to sell?

By breaking down the components of past returns, we can also attempt to project Apple's future returns.

Assume, for a moment, that Apple continues its impressive 7.5% growth rate for the next decade—a highly optimistic scenario. This growth rate over the last 7 years was fueled by the creation of a new wearables business and a shift to more premium products. However, with nominal GDP growing at roughly 5%, it will be challenging for Apple to consistently outpace that. But for the sake of this analysis, let's assume they can maintain this growth.

In the past year, Apple reduced its share count by 2.5%. Given its strong free cash flow, let's assume they continue this pace of buybacks for the next decade.

The stock also pays a dividend yield of 0.47%. Let's assume this dividend grows in line with sales, at 7.5% annually.

Next, we need to consider the speculative return. It’s one thing to factor in multiple expansion when the stock trades at 11.5x earnings and 2.6x sales, but it’s much riskier at its current valuation of 32.4x earnings and 8.5x sales. Instead, let's assume Apple reverts to its average valuation since 2015, with a price-to-sales ratio of 4.75x and a P/E of 20.6x.

Under these assumptions, the projected CAGR is around 4.74%.

However, even this projection is optimistic. It’s unlikely that Apple can sustain a 7.5% growth rate for another decade, and assuming a P/E of 20.6 and a price-to-sales ratio of 4.75x is still quite generous.

There’s little margin of safety in this outlook.

If growth were to slow to 5% and the valuation multiples return to 2015 levels, the CAGR drops to -3.72%.

In an optimistic scenario, Buffett might hold onto Apple and achieve a return of 4.74%. In an equally plausible scenario, Buffett could actually lose money over the next 10 years.

This outcome is highly speculative. It’s a far cry from buying a deeply undervalued stock that can deliver a 14% return without relying on multiple expansion, with the potential for additional gains if the multiple improves, which was the case with Apple in early 2016.

Meanwhile, he could invest in a 1-year Treasury today with a guaranteed, risk-free return of 4.5%.

Viewed through this lens, Buffett’s decision to sell becomes quite clear. The potential returns from holding Apple at its current valuation simply do not justify the risk, especially when safer, more attractive alternatives are available.

Implications

Many people see Buffett's sale of Apple as a signal about the broader stock market's value. (Though, it’s debatable whether they truly believe this or are just chasing clicks.)

But this interpretation misses the mark. Buffett isn't focused on evaluating the entire market; his strategy revolves around assessing the value of individual companies.

Each stock is priced based on its unique prospects and current market conditions—just because one stock is overvalued doesn’t mean the whole market is.

Moreover, Buffett's decision to sell Apple isn't a critique of the company’s business fundamentals. Apple might be overvalued at the moment, but that doesn’t change the fact that it’s a fantastic company.

This distinction is often challenging for investors to grasp: a great business doesn’t automatically make for a great investment. It all hinges on the price you pay.

The key takeaway: Even a world-class business can yield poor returns if purchased at too high a price.

Disclaimer

Nothing on this substack is investment advice.

The information in this article is for information and discussion purposes only. It does not constitute a recommendation to purchase or sell any financial instruments or other products. Investment decisions should not be made with this article and one should take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular person or institution.

Investors should obtain advice based on their own individual circumstances from their own tax, financial, legal, and other advisers about the risks and merits of any transaction before making an investment decision, and only make such decisions on the basis of the investor’s own objectives, experience, and resources.

The information contained in this article is based on generally-available information and, although obtained from sources believed to be reliable, its accuracy and completeness cannot be assured, and such information may be incomplete or condensed.

Investments in financial instruments or other products carry significant risk, including the possible total loss of the principal amount invested. This article and its author do not purport to identify all the risks or material considerations that may be associated with entering into any transaction. This author accepts no liability for any loss (whether direct, indirect, or consequential) that may arise from any use of the information contained in or derived from this website.

"I'm also into that. Sounds great!"