Are Markets Broken?

David Einhorn ignited a firestorm on Twitter with his bold assertion that "markets are broken” on Barry Ritholtz’s Masters in Business Podcast.

I disagree with his assertion, but it’s still a great interview with a skilled investor that you should check out. Here it is:

By the way, I understand that “firestorm on Twitter/X/whateverEloniscallingitnow” is sure to make anyone in the real world roll their eyes.

Einhorn's argument revolves around the notion that the increasing prevalence of passive ownership in the market is leading to distortions.

With more investors embracing passive approaches, the pool of active participants engaging in genuine security analysis dwindles, leading to peculiar market dynamics. This trend is further reinforced by the steady inflow of funds into 401(k) accounts, fueling a continuous upward momentum in the largest stocks.

The shift to passive results from investors realizing that their active managers often struggle to outperform the market. Evidence from sources like SPIVA data, which shows that over 90% of fund managers fail to beat their benchmark, as well as insights from the Buffett bet, where the average 'hedge fund' performed poorly compared to a simple 60/40 portfolio in 2008 and delivered a less than 3% average return from 2007-17.

Moreover, with easy access to benchmark performance data via the internet, investors can readily compare their manager's returns to the benchmark, leading many to question the value of paying high fees for underwhelming results.

That was a much more difficult thing to do before the internet. Now, we have tools like Portfolio Visualizer, which make it very easy to look up this data.

Meanwhile, the notion that 'markets are broken' serves as a rallying cry for active managers, offering them a convenient excuse for underperformance and outflows. It shifts the blame away from their own strategies, implying that the culprit is the distortion caused by the influx of passive investments rather than their selection of poorly performing stocks.

In essence, if your investment isn't yielding the desired results, it's not your fault. The scarcity of active investors means there may not be enough discerning individuals to recognize the merit of your investment idea.

I think it’s important to consider whether or not this is correct. As someone conducting security analysis, if no one else is doing it, then my efforts might be a waste of time.

Alternatively, it might create distortions that I should be seizing upon.

High level, I don’t believe that markets are broken. Here is why:

#1: There is A Dearth of ‘Guaranteed High Return’ Situations

To his credit, Einhorn refrains from simply complaining about this phenomenon. He argues that he realized this phenomenon and changed his strategy successfully because of it.

His track record is strong over recent years. He attributes this success to a pivot towards extreme value investing in response to market dynamics.

During the interview, he highlights his focus on stocks boasting a P/E of 5 coupled with aggressive stock buybacks (20%/year).

That is a situation that should work no matter what is going on in the broader market. Assuming that the business doesn’t have massive risks, this situation is essentially guaranteed profits.

One notable instance where Einhorn capitalized on such an opportunity was with Dillard's stock. Back in 2021, Dillard's traded at a modest 6 P/E ratio, and their share count had decreased by approximately 29% since 2019. The stock has transformed a $10,000 investment into $72,000.

Regrettably, opportunities like the one presented by Dillard's are not widespread. The undervaluation of Dillard's was an outcome of the retail sector falling out of favor, compounded by an exaggerated response to the impact of COVID.

In typical market conditions, finding such situations is challenging, especially if you operate outside the nano or micro cap market realms. Factors such as large country-exposure risk (as in the case of China or Russian stocks before the invasion), extreme cyclicality in a stock during a boom, and concerns about potential secular decline are usually a staple of stocks with a P/E of 5 or less.

In fact, scanning Einhorn’s current positions, I can’t find a single one that’s anything like that Dillards investment.

If the markets were genuinely broken, I would expect to frequently find opportunities like the one described - where stocks with a P/E of 5 are buying back 20% of their stock - in smaller market capitalizations or outside of indexes.

In the ‘markets are broken and no one is doing security analysis’ scenario, capital would naturally gravitate towards the largest stocks and present ‘guaranteed high return situations’ (like a P/E of 5 buying back 20% of their stock) across lower market caps. If no one is doing the work to find these situations, then they would be available to be seized upon.

However, this is not the case. I’ve run screens looking for them. Einhorn, based on his current holdings, can’t find them, either.

The scarcity of such situations suggests that investors are indeed conducting genuine security analysis. When things start to get really off the rails in a stock, investors intervene.

Similarly, if passive flows were truly distorting the market to an extreme degree, another straightforward arbitrage opportunity would arise: buy the stocks as they enter the index and short the ones exiting the index.

This strategy was effective in the 1990’s but has since been arbitraged away. If passive flows were distorting the market, I would expect this phenomenon to intensify. Instead, it’s disappearing.

If passive investing were to reach a level of distortion as claimed by Einhorn, one would expect to see more 'guaranteed free money' opportunities, akin to the example of a stock with a 20% buyback and a 5 P/E ratio or mechanically buying stocks before they enter an index and shorting those that leave the index. This would likely lead to significant outperformance for active investors, potentially altering the market's dynamics back to active managers in the process.

In other words, markets don’t give away free money as a result of distortions caused by passive flows. I wish they did!

#2: Stocks still follow fundamentals

On this platform, I conduct weekly analyses of various companies. Within each post, I dedicate a section to examining the historical returns of the stock and the drivers behind those returns.

Primarily, these returns are typically driven by fundamental performance.

The returns of stocks can be broken down to the following components:

Fundamental business performance.

Shareholder yield - dividends and buybacks.

Changes in valuation multiples.

Through conducting this exercise over the span of several years, I've discovered that in the majority of cases, stock performance correlates closely with fundamental factors. This sentiment echoes the wisdom of Ben Graham's concept of the "long term weighing machine."

I used to hold a somewhat tentative belief in this idea. It was the kind of thing that sounded right and I thought was correct.

After immersing myself in the analysis of a new company each week for the last few years, I now believe in my bones.

Even fluctuations in multiples, though they may occasionally exhibit irrational behavior, can typically be traced back to rational responses to the underlying business dynamics. More often than not, there exists a clear explanation for shifts in multiples, which often stem from changes in margins, capital allocation decisions, business developments, or other fundamental developments.

Recently on Twitter, I highlighted the fact that Google shares have surged by 160% over the past five years, mirroring a similar increase in its earnings per share.

While some accused me of cherry-picking data, there's still truth in the observation. Google serves as a compelling case study: despite being a major stock often criticized as being in a bubble, its price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio is pretty close to where it was 5 years ago. It stood at 24 at the end of 2018 and sits at 27 presently (with a wild up and down ride in the middle), and it doesn't offer substantial shareholder yield. As a result of this (a similar P/E at the start and beginning, not much shareholder yield), the returns have largely reflected the growth in EPS.

This methodology is inspired by the legendary investor Peter Lynch. In his book Beating the Street, Lynch advocates plotting EPS on one axis against the stock price on the other, illustrating how most stocks tend to fluctuate around an earnings growth line. Over long periods (over 5 years), the two tend to be extremely similar for most stocks.

You can delve into my archives on this site and witness this methodology in action repeatedly. I've profiled nearly 100 stocks on this platform, and in each instance, there's a compelling argument that the stock's performance is rooted in fundamentals.

Even in scenarios where a significant portion of the return stems from valuation increases, these shifts in valuation typically reflect genuine fundamental developments.

This holds true even for very expensive stocks, such as Tesla (which saw a staggering 293% increase in revenues since 2019 and shifted to positive free cash flow) or NVIDIA (with revenues surging over 400% since 2019 and return on equity skyrocketing from 26% to 91%).

Whether the market's response to improvements in Tesla and NVIDIA constitutes an overreaction is a separate discussion altogether. Nonetheless, the fundamental fact remains: these businesses have undergone significant improvement, and the market has responded.

Even if NVIDIA and Tesla are currently overvalued (which I tend to believe they are), this phenomenon is nothing new in the realm of markets. Throughout history, there have always been stocks that garner excessive enthusiasm from investors.

Consider the late 1990s when passive investing held a trivial share of the market. In that environment, companies like Cisco and Microsoft reached astronomical valuations by 2000, resulting in a prolonged period of stagnant returns despite positive business developments. This wasn't attributable to passive flows; rather, it was fueled by the excessive enthusiasm of active managers.

The considerable fluctuation of multiples for large companies in response to business developments underscores the continued presence and influence of active investors. If active investors were truly extinct, there would be no one left to fuel the enthusiasm surrounding a high-performing company or grow despondent about the poorly performing firms.

#3: Passive Isn’t Big Enough

At what point does passive investing become so large that markets are extremely distorted?

Let’s start with theory and then move onto the current state of the market.

Theoretically, what percentage passive investing might become a tipping point for market distortion?

The anonymous author of the Philosophical Economics blog explored this theoretical scenario extensively back in 2016. His conclusion: “Where is that minimum level? In my view, far away from the current level, at least at current fee rates. If I had to randomly guess, I would say somewhere in the range of 5% active, 95% passive. If we include private equity in the active universe, then maybe the number is higher–say, 10% active, 90% passive.”

Therefore, theoretically speaking, passive investing still has a considerable way to go before markets might be considered 'broken,' as Einhorn suggests.

In real world terms, where do we currently stand? How much of the market is passive?

Estimates vary. According to this Bloomberg article from 2021, passive investing began to outpace active around 2018. The article indicates that approximately 54% of US domestic equity funds are now passive. This "over 50%" metric is frequently cited, hinting at a potential tipping point, as the majority of assets under management (AUM) are now in passive funds.

While the focus often revolves around active management as a percentage of total AUM in stock funds, a deeper analysis reveals a different picture when considering the total ownership of the stock market.

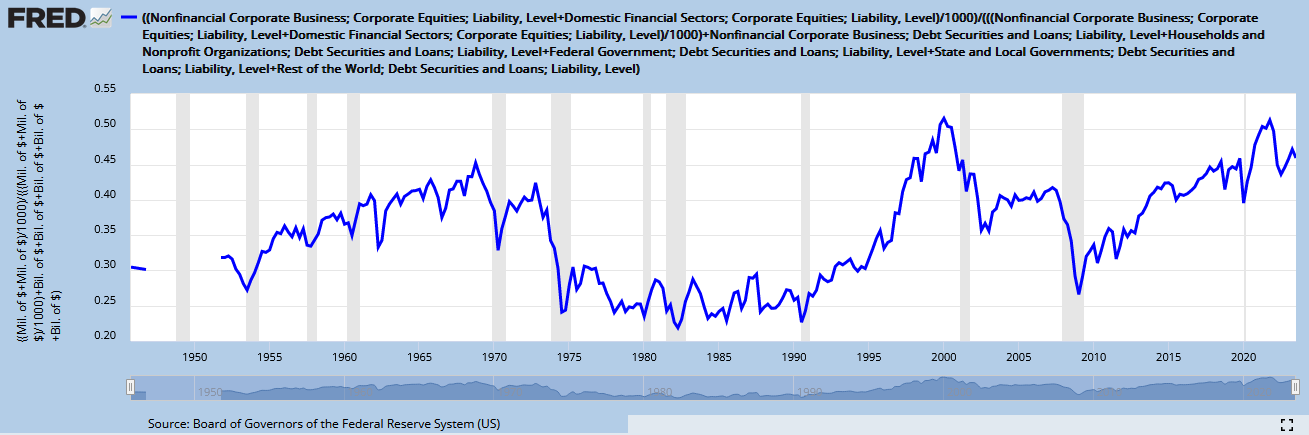

Eric Balchunas, whom I had the opportunity to interview on my podcast, delved into this topic extensively in his book The Bogle Effect. He suggests that when breaking down the total ownership of the US stock market, equity index funds represent only 17% of the market as of 2021.

Balchunas further notes that this figure can rise to 30% if we include institutional investors such as pensions, endowments, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, and family offices. Is 30% too much? I don’t think it is.

A skeptic might argue that other investors, such as households and business founders, don't significantly influence market prices because they're not actively participating in the market daily. However, I disagree with this notion. While they may not engage in daily trading activities, their occasional buying or selling of stocks can still impact prices. They do indeed have an impact, albeit not as much as stock funds.

#4: Passive Money Isn’t Really Passive

I don’t subscribe to the notion that all the capital invested in US indexes is truly passive, with investors simply parking their money for long-term exposure to the genuine returns of the stock market and then ignoring the gyrations of the market.

While many investors grasp the theory behind passive investing, few actually adhere to it in practice. Instead, they tend to react to the market's performance and adjust their allocations accordingly.

JPMorgan conducted a study over 20 years on the average returns realized by investors. The results were sobering: the average investor significantly underperforms across the board. Their average return sits at a mere 3.6%, compared to the S&P 500's compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.5% and bond returns of 4.3%.

What's driving this underperformance? I believe that it largely boils down to market timing. Investors frequently engage in activities like reducing their stock allocation during periods like COVID or the 2008 financial crisis, effectively locking in substantial losses at the worst moments.

Conversely, they tend to become overly optimistic during bull markets and increase their equity exposure. When it comes to owning ETFs in brokerage accounts, it's doubtful that many individuals are truly committed to buy-and-hold strategies like holding VOO or VTI for the long term.

Another way to measure this is to examine the average investor allocation to equities. From my observations, it appears that investors are continually fine-tuning their allocations, responding to market conditions.

Passive ownership of the market witnessed a surge during the 2000s; however, this didn't prevent the average allocation from shifting dramatically, plummeting from over 50% to under 30% in response to events such as the collapsing tech bubble and the global financial crisis.

I'm confident that over the next 20 years, we'll see another instance where the allocation dips below 30%, followed by another bull market where it rises back up to 50%.

While passive and low-fee investment vehicles are available, the capital ultimately belongs to human beings who continue to respond to conditions with the age-old emotions of fear and greed.

Investors' behaviors are marked by cycles of fear and enthusiasm, reflecting decidedly active tendencies.

This behavior becomes particularly apparent when considering the constant shifts in asset class allocations. Investors regularly move their money between asset classes such as US stocks, international stocks, value stocks, growth stocks, gold, treasuries, high-yield bonds, etc.

In a world where everyone is passive, would so many investors remain enthusiastic about ARKK? Would so many speculate about bitcoin? Would they argue about whether growth or value will outperform? Debates and speculation rage about all of these investments.

Speculation is alive and well even though passive vehicles might be the tool to move capital between asset classes, sectors, and strategies.

Conclusion

I don’t believe that passive flows are distorting the market significantly.

Ben Graham's timeless analogy of the market as a short-term voting machine and a long-term weighing machine still appears to underpin market dynamics. Meanwhile, investors continue to exhibit emotional responses, actively influenced by fear and greed.

Regardless of whether you share my perspective, Einhorn's emphasis on seeking out extreme value underscores an important principle. In my view, as an active investor, this pursuit of value should be a fundamental strategy regardless of market conditions, whether there's a passive bubble or not.

If you're an active investor and you're not actively seeking out value, then what exactly is your strategy? Seeking out value is what you should be doing regardless of whether passive flows are distorting the market or not.

Disclaimer

Nothing on this substack is investment advice.

The information in this article is for information and discussion purposes only. It does not constitute a recommendation to purchase or sell any financial instruments or other products. Investment decisions should not be made with this article and one should take into account the investment objectives or financial situation of any particular person or institution.

Investors should obtain advice based on their own individual circumstances from their own tax, financial, legal, and other advisers about the risks and merits of any transaction before making an investment decision, and only make such decisions on the basis of the investor’s own objectives, experience, and resources.

The information contained in this article is based on generally-available information and, although obtained from sources believed to be reliable, its accuracy and completeness cannot be assured, and such information may be incomplete or condensed.

Investments in financial instruments or other products carry significant risk, including the possible total loss of the principal amount invested. This article and its author do not purport to identify all the risks or material considerations that may be associated with entering into any transaction. This author accepts no liability for any loss (whether direct, indirect, or consequential) that may arise from any use of the information contained in or derived from this website.